Books Reviews

Previously published in the monthly e-newsletter Digestible Bits & Bites. Subscribe here free of charge.

Index (reviews are below)

- 100 Million Years of Food: What Our Ancestors Ate and Why It Matters Today by Stephen Le

- Acorn: Vegetables Re-Imagined, Seasonal Recipes from Root to Stem by Shira Blustein & Brian Luptak

- Afternoon Tea: A History and Guide to the Great Edwardian Tradition by Vicky Straker

- American Cake by Anne Byrn

- Aran: Recipes and Stories from a Bakery in the Heart of Scotland by Flora Shedden

- At the First Table: Food and Social Identity in Early Modern Spain by Jodi Campbell

- Baking at the 20th Century Cafe by Michelle Polzine

- Baking Day with Anna Olson: Recipes to Bake Together by Anna Olson

- Baking Powder Wars: The Cutthroat Food Fight That Revolutionized Cooking by Linda Civitello

- Baking with Bruno, A French Baker’s North American Love Story by Bruno Feldeisen

- Baking Yesteryear: The best recipes from the 1900s to the 1980s by B. Dylan Hollis

- Being Neighbours: Cooperative Work and Rural Culture, 1830–1960 by Catharine Anne Wilson

- Bene Appétit: The Cuisine of the Indian Jews by Esther David

- Berries by Victoria Dickenson

- Birdseye: The Adventures of a Curious Man by Mark Kurlansky

- The Bite Me Balance Cookbook: Wholesome Daily Eats & Delectable Occasional Treats by Julie Albert & Lisa Gnat

- Blood, Bones & Butter: The Inadvertent Education of a Reluctant Chef by Gabrielle Hamilton

- Boire le Québec by Rose Simard

- Bong Appétit by the editors of Munchies & Elise McDonough

- The Book of Chocolate: The Amazing Story of the World’s Favorite Candy by HP Newquist

- Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of Foods We Love by Simran Sethi

- Breakfast Cereal: A Global History by Kathryn Cornell Dolan

- Brewed in the North: A History of Labatt’s by Matthew J. Bellamy<

- Brewing Revolution, Pioneering the Craft Beer Movement by Frank Appleton

- Butter: A Rich History by Elaine Khosrova

- Canada’s Food Island: A Collection of Stories and Recipes from Prince Edward Island by Stuart Hickox

- Canadian Literary Fare by Nathalie Cooke & Shelley Boyd with Alexia Moyer

- Canadian Spirits: The Essential Cross-Country Guide to Distilleries, Their Spirits, and Where to Imbibe Them by Stephen Beaumont & Christine Sismondo

- The Canadian Receipt Book, Containing over 500 Valuable Receipts for the Farmer and the Housewife, First Published in 1867, ed. Jen Rubio

- Cannabis Cuisine, Bud Pairings of a Born Again Chef by Andrea Drummer

- Celtia, histoire d’une bière de Tunisie … De Luxembourg à Tunis by Paul Nicolas

- Cherry by Constance L. Kirker & Mary Newman

- Chez Lesley: Mes secrets pour tout réussir en cuisine by Lesley Chesterman

- Chillies: A Global History by Anne Arndt Anderson

- Chop Suey Nation: The Legion Café and Other Stories from Canada’s Chinese Restaurants by Ann Hui

- The Clever Gut Diet Cookbook by Clare Bailey & Joy Skipper

- The Coastal Forager’s Cookbook: Feasting in the Pacific Northwest by Chef Robin Kort

- Cocktails, A Still Life: 60 Spirited Paintings & Recipes by Christine Sismondo & James Waller, Art by Todd M. Casey

- Cod, A Global History by Elisabeth Townsend

- Cooking alla Giudia: A Celebration of the Jewish Food of Italy by Benedetta Jasmine Guetta

- The Cooking Gene: A Journey through African American Culinary History of the Old South by Michael Twitty

- A Cornucopia of Fruit and Vegetables: Illustrations from an Eighteenth-Century Botanical Treasury by Caroline Ball

- Craft: An Argument: Why the Term “Craft Beer” Is Completely Undefinable, Hopelessly Misunderstood and Absolutely Essential by Pete Brown

- Culinary Herbs: Grow, Preserve, Cook! by Yvonne Tremblay

- Curry: Eating, Reading, and Race by Naben Ruthnum

- Dining out with History: At Atlantic Canada’s Historical Sites by Jan Feduck

- Dinner with Dickens, Recipes Inspired by the Life and Work of Charles Dickens by Pen Vogler

- Distilled: A Natural History of Spirits by Rob DeSalle & Ian Tattersall

- The Distilleries of Vancouver Island: A Guided Tour of West Coast Craft and Artisan Spiritsby Marianne Scott

- Don’t Worry, Just Cook by Bonnie Stern & Anna Rupert

- Don Mills: From Forests and Farms to Forces of Changeby Scott Kennedy

- The Double Happiness Cookbook: 88 Feel-Good Recipes and Food Stories by Trevor Lui

- Eat, Habibi, Eat! Fresh Recipes for Modern Egyptian Cooking by Shahir Massoud

- Eating Like a Mennonite by Marlene Epp

- Egg: A Dozen Ovatures by Lizzie Stark

- L’érable et la perdrix: l’histoire Culinaire du Québec à travers ses aliments by Elisabeth Cardin & Michel Lambert

- Essential Fondue Cookbook: 75 Decadent Recipes to Delight and Entertain by Erin Harris

- The Fair Trade Ingredient Cookbook by Nettie Cronish

- Fasting and Feasting: The Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray by Adam Federman

- Fats: A Global History by Michelle Phillipov

- Feasting Wild by Gina Rae La Cerva

- Fermented Foods: The History and Science of a Microbiological Wonder by Christine Baumgarthuber

- Finding the Flavors We Lost: From Bread to Bourbon, How Artisans Reclaimed American Food by Patric Kuh

- Les filles Fattoush: La cuisine syrienne, une cuisine de coeur by Adelle Tarzibachi

- First Catch Your Gingerbread by Sam Bilton

- Fish and Chips: A History by Panikos Panayi

- The Five Bottle Bar: A Simple Guide to Stylish Cocktails by Jessica Schacht

- The Flavor Equation, The Science of Great Cooking Explained by Nik Sharma

- The Food Adventurers: How Around the World Travel Changed The Way We Eat by Daniel E. Bender

- The Food Almanac: Recipes and Stories for a Year at the Table by Miranda York

- Food and Museums, edited by Nina Levent & Irina D. Mihalache

- The Food in Jars Kitchen by Marisa McClellan

- Food in the Gilded Age: What Ordinary Americans Ate by Robert Dirks

- Food in Time and Place: The American Historical Association Companion to Food History, edited by Paul Freedman, Joyce E. Chaplin & Ken Albala

- Food Matters: Alonso Quijano’s Diet and the Discourse of Food in Early Modern Spain by Carolyn A. Nadeau

- Food on the Move, Dining on the Legendary Railway Journeys of the World, edited by Sharon Hudgins

- Food Through The Ages: A Popular History by Mike Gibney

- Fool’s Gold: A History of British Saffron by Sam Bilton

- France Is a Feast: The Photographic Journey of Paul and Julia Child by Alex Prud’homme & Katie Pratt

- The French Laundry, Per Se by Thomas Keller et al.

- From Dismal Swamp to Smiling Farms: Food, Agriculture and Change in the Holland Marsh by Michael Classens

- From Scratch: Adventures in Harvesting, Hunting, Fishing, and Foraging on a Fragile Planet by David Moscow & Jon Moscow

- The Fruitful City: The Enduring Power of the Urban Food Forest by Helena Moncrieff

- F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Taste of France: Recipes Inspired by the Cafés and Bars of Fitzgerald’s Paris and the Riviera in the 1920s by Carol Hilker

- Ghetto Gastro Presents Black Power Kitchen by Jon Gray, Pierre Serrao, Lester Walker & Osayi Endolyn

- The Ghost Orchard: The Hidden History of the Apple in North America by Helen Humphreys

- Gifts of the Gods: A History of Food in Greece by Andrew & Rachel Dalby

- The Gilded Age Cookbook: Recipes and stories from America’s Golden Era by Becky Libourel Diamond

- Good Food, Healthy Planet: Your Kitchen Companion to Simple, Practical, Sustainable Cooking by Puneeta Chhitwal-Varma

- Grandma’s Cookies, Cakes, Pies and Sweets: The Best of Canada’s East Coast by Alice Burdick

- The Hamilton Cookbook: Cooking, Eating & Entertaining in Hamilton’s World by Laura Kumin

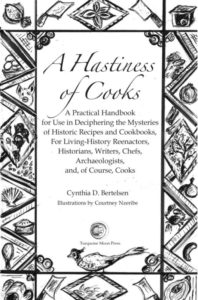

- A Hastiness of Cooks, A Practical Handbook… by Cynthia D. Bertelsen

- Have You Eaten Yet? Stories from Chinese Restaurants Around the World by Cheuk Kwan

- Hawksworth: The Cookbook by Chef David Hawksworth with Chef Stéphanie Noël & Jacob Richler.

- Healing Cannabis Edibles: Exploring the Synergy of Power Herbs by Ellen Novack & Pat Crocker

- Heaven on the Half Shell, Second Edition by David George Gordon, Samantha Larson & Maryann Barron Wagner

- The Hebridean Baker by Coinneach MacLeod

- Herb: Mastering the Art of Cooking with Cannabis by The Stoner’s Cookbook, Melissa Parks & Laurie Wolf

- Herbs around the Mediterranean by The St. Louis Herb Society

- Hippie Food by Jonathan Kauffman

- A History of Bread Consumers, Bakers and Public Authorities Since The 18th Century by Peter Scholliers

- Honey from a Weed: Fasting and Feasting in Tuscany, Catalonia, the Cyclades and Apulia by Patience Gray

- How to Cook the Victorian Way with Mrs. Crocombe by Annie Gray & Andrew Hann

- How to Dress an Egg: Surprising and Simple Ways to Cook Dinner by Ned Baldwin and Peter Kaminsky

- How Would You Like Your Mammoth? 12,00 Years of Culinary History in 50 Bite-Size Essays by Uta Seeburg

- Hummus: A Global History by Harriet Nussbaum

- I Hear She’s a Real Bitch by Jen Agg

- Ingredients for Revolution: A History of American Feminist Restaurants, Cafés, and Coffeehouses by Alex D. Ketchum

- Invitation to a Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food by Fuchsia Dunlop

- Island Eats—Signature Chef’s Recipes from Vancouver Island and the Salish Sea by Dawn Postnikoff & Joanne Sasvari

- Jam Bake: Inspired Recipes for Creating and Baking with Preserves by Camilla Wynne

- Jam, Jelly and Marmalade: A Global History by Sarah B. Hood

- Je suis pas cheffe, pis toi non plus by Geneviève Pettersen

- King Solomon’s Table: A Culinary Exploration of Jewish Cooking from around the World by Joan Nathan

- The King’s Peas: Delectable Recipes and Their Stories from the Age of Enlightenment by Meredith Chilton

- The Kitchen: A Journey Through Time—and the Homes of Julia Child, Georgia O’Keeffe, Elvis Presley and Many Others—In Search of the Perfect Design by John Ota

- Kitchen Party by Mary Berg

- Kosher Style: Over 100 Jewish Recipes for the Modern Cook by Amy Rosen

- K pour Katrine: Le livre de recettes by Katrine Paradis & Margaux Verdier

- Légumes Asiatiques: Jardiner Cuisiner Raconter by Caroline, Stéphanie & Patricia Wang

- The Lemon Apron Cookbook: Seasonal Recipes for the Curious Home Cook by Jennifer Emilson

- The Little Prairie Book of Berries: Recipes for Saskatoons, Sea Buckthorn, Haskap Berries and More by Sheryl Normandeau

- Little Critics: What Canadian Chefs Cook for Kids (and kids will actually eat) by Joanna Fox

- Little Italy: Italian Finger Food by Nicole Herft

- Lost Feast: Culinary Extinction and the Future of Food by Lenore Newman

- The Lost Supper: Searching for the future of food in the flavors of the past by Taras Grescoa

- Madrid: A Culinary History by Maria Paz Moreno

- Mandy’s Gourmet Salads: Recipes for Lettuce and Life by Mandy Wolfe, Rebecca Wolfe and Meredith Erickson

- The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard by John Birdsall

- Martha Lloyd’s Household Book: The Original Manuscript from Jane Austen’s Kitchen, introduced, transcribed & annotated by Julienne Gehrer. Foreword by Deirdre Le Faye

- Meals, Music, and Muses: Recipes from My African American Kitchen by Alexander Smalls & Veronica Chambers

- Melon: A Global History by Sylvia Lovegren

- Menno-Nightcaps: Cocktails Inspired by that Odd Ethno-Religious Group You Keep Mistaking for the Amish, Quakers or Mormons by S. L. Klassen

- The Miracle of Salt: Recipes and Techniques to Preserve, Ferment, and Transform Your Food by Naomi Duguid

- Miss Eliza’s English Kitchen: A Novel of Victorian Cookery and Friendship by Annabel Abbs

- Montréal l’hiver: Recettes et récits tricotés serrés by Susan Semenak

- Mrs Beeton and Mrs Marshall: A Tale of Two Victorian Cooks by Emma Kay

- Mrs Dalgairns’s Kitchen: Rediscovering “The Practice of Cookery” edited by Mary F. Williamson with modernized recipes by Elizabeth Baird

- My Ackee Tree – A Chef’s Memoir of Finding Home in the Kitchen by Suzanne Barr with Suzanne Hancock

- National Dish: Around the world in search of food, history, and the meaning of home by Anya von Bremzen

- The National Trust Book of Scones: 50 Delicious Recipes and Some Curious Crumbs of History by Sarah Clelland

- New Indian Basics: 100 Traditional and Modern Recipes from Arvinda’s Family Kitchen by Preena Chauhan & Arvinda Chauhan

- Noma 2.0 – Vegetable Forest Ocean by René Redzepi, Mette Søberg & Junichi Takahashi

- Nose Dive: A Field Guide to the World’s Smells by Harold McGee

- The Nutmeg Trail: Recipes and Stories Along the Ancient Spice Routes by Eleanor Ford

- Oishii: The History of Sushi by Eric C. Rath

- Onions and Garlic: A Global History by Martha Jay

- Only In Saskatchewan by Naomi Hansen

- On the Road with the Cooking Ladies: Let’s Get Grilling by Phyliss Hinz & Lamont Mackay

- Ottolenghi Flavor: A Cookbook by Yotam Ottolenghi, Ixta Belfrage & Tara Wigley

- Out of Old Ontario Kitchens by Lindy Mechefske

- Outlander Kitchen II: Journey to the New World and Back Again by Theresa Carle-Sanders

- Painting the Plate: 52 Recipes inspired by great works of art from Mark Rothko, Frida Kahlo and many more by Felicity Souter

- Pies, Glorious Pies by Maxine Clark

- Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food by Jeffrey M. Pilcher

- The Prairie Table by Karlynn Johnston

- Precious Cargo: How Foods from the Americas Changed the World by Dave DeWitt

- Preserving on Paper: Seventeenth-Century Englishwomen’s Receipt Books, edited by Kristine Kowalchuk

- Provence to Pondicherry by Tessa Kiros

- Prune by Gabrielle Hamilton

- Pure Adulteration: Cheating on Nature in the Age of Manufactured Food by Benjamin R. Cohen

- The Pueblo Food Experience Cookbook: Whole Food of Our Ancestors, edited by Roxanne Swentzell & Patrician M. Perea

- Racines by Fisun Ercan

- Recipes and Everyday Knowledge: Medicine, Science and the Household in Early Modern England by Elaine Leong

- Recipes and Reciprocity, Building Relationships in Research, edited by Hannah Tait Neufeld & Elizabeth Finnis

- Recipes for Victory: Great War Food from the Front and Kitchens Back Home in Canada, ed. Elizabeth Baird & Bridget Wranich

- Recipes, Inspiration, Stories. Liberté: When Yogourt Makes the Difference By Liberté

- The Redpath Canadian Bake Book by Redpath Sugar

- Rhubarb: New and Classic Recipes for Sweet and Savory Dishes by Søren Staun Petersen

- Rose Murray’s Comfortable Kitchen Cookbook: Easy, Feel-Good Food for Family and Friends by Rose Murray

- Salad Pizza Wine by Janice Tiefenbach, Stephanie Mercier Voyer, Ryan Gray & Marley Sniatowsky

- Salt Beef Buckets: A Love Story by Amanda Dorothy Jean Bulman

- Shelf Love: Recipes to Unlock the Secrets of Your Pantry, Fridge, and Freezer by Noor Murad & Yotam Ottolenghi

- Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen by Rebecca May Johnson

- Smitten Kitchen Keepers: New Classics for Your Forever Files by Deb Perelman

- Snacks: A Canadian Food History by Janis Thiessen

- The Social Archaeology of Food: Thinking about Eating from Prehistory to the Present by Christine A. Hastorf

- Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America by Laura Shapiro

- Speaking in Cod Tongues: A Canadian Culinary Journey by Lenore Newman

- A Square Meal: A Culinary History of the Great Depression by Jane Ziegelman & Andrew Coe

- Staging the Table in Europe: 1500–1800 by Deborah L. Krohn

- Super Sourdough: The Foolproof Guide to Making World-Class Bread at Home by James Morton

- Sweet Malida: Memories of a Bene Israel Woman by Zilka Joseph

- Taste: A Philosophy of Food by Sarah E. Worth

- Taste Makers: Seven Immigrant Women Who Revolutionized Food in America by Mayukh Sen

- The Taste of Longing, Ethel Mulvany and Her Starving Prisoners of War Cookboo by Suzanne Evans

- Taste of Persia: A Cook’s Travels Through Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, and Kurdistan by Naomi Duguid

- Tasting Rome, Fresh Flavors & Forgotten Recipes from an Ancient City by Katie Parla & Kristina Gill

- Tawâw, Progressive Indigenous Cuisine by Shane M. Chartrand & Jennifer Cockrall-King

- T-Bone Whacks and Caviar Snacks: Cooking with Two Texans in Siberia and the Russian Far East by Sharon Hudgins

- Tenderheart: A Cookbook About Vegetables and Unbreakable Family Bonds by Hetty Lui McKinnon

- Ten Tomatoes That Changed the World : A History by William Alexander

- Tequila: A Global History by Ian Williams

- That Noodle Life: Soulful, Savory, Spicy, Slurpy by Mike Le & Stephanie Le

- A Thirst for Wine and War—The Intoxication of French Soldiers on the Western Front by Adam D. Zientek

- Tools for Food: The Stories Behind the Objects that Influence How and What We Eat by Corinne Mynatt

- Tout sur les gins du Québec by Patrice Plante

- True to the Land: A History of Food in Australia by Paul van Reyk

- The Two Spoons Cookbook: More than 100 French-inspired Recipes by Hannah Sunderani

- Uncertain Harvest: The Future of Food on a Warming Planet by Ian Mosby, Sarah Rotz & Evan D.G. Fraser

- The Unofficial Bridgerton Book of Afternoon Tea by Katherine Bebo

- The Up-to-Date Sandwich Book: 400 Ways to Make a Sandwich - A Faithful Recreation of the Original 1909 Edition by Eva Greene Fuller

- United Tastes: The Making of the First American Cookbook by Keith Stavely & Kathleen Fitzgerald

- Via Carota: A Celebration of Seasonal Cooking from the Beloved Greenwich Village Restaurant by Jody Williams & Rita Sodi with Anna Kovel

- We Are What We Eat: A Slow Food Manifesto by Alice Waters with Bob Carrau & Cristina Mueller

- Well Seasoned: A Year’s Worth of Delicious Recipes by Mary Berg

- Welsh Food Stories by Carwyn Graves

- What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings, edited by John Lorinc

- Where the River Narrows: Classic French and Nostalgic Québécois Recipes from St. Lawrence Restaurant, by J-C Poirier with Joie Alvaro Kent

- Where We Ate: A Field Guide To Canada’s Restaurants, Past And Present by Gabby Peyton

- Why Fast? The pros and cons of restrictive eating by Christine Baumgarthuber

- Why We Cook: Women on Food, Identity, and Connection by Lindsay Gardner

- You and I Eat the Same: On the Countless Ways Food and Cooking Connect Us to One Another, edited by Chris Ying

- You Wanna PIEce of Me? More than 100 Seriously Tasty Recipes for Sweet and Savory Pies by Jenell Parsons

- Zaatari: Culinary Traditions of the world’s largest Syrian refugee camp by Karen E. Fisher

The Reviews

Invitation to a Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food by Fuchsia Dunlop (W.W. Norton, 2023). Reviewed by Ivy Lerner-Frank, pictured above.

Fuchsia Dunlop was the first Western student to train at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine in the ‘90s. Her memoir about that formative period, Shark’s Fin & Sichuan Pepper (she inscribed my copy in 2009, while I was living in Beijing) complemented her other cookbooks about Hunan, Sichuan, Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. The evocative instructions in these volumes—”stir until it smells wonderful” is one of my favourites—provide the reader and home cook with unique, accessible windows into Chinese regional cooking. Dunlop’s third book, Every Grain of Rice, a home cooking manual, is nothing less than a Chinese Joy of Cooking; my own beloved volume is falling apart and oil-splattered.

With this, her latest, written during the years of COVID confinement, she turns her pen to the banquet that is Chinese gastronomy, drawing on travel and interviews from her decades living in China. Going literally from farm to table, she provides an extensively detailed, completely accessible narrative, sharing her profound understanding of and fascination for the history, traditions, language and philosophy of Chinese food.

With clear and often sensuous prose, Dunlop explores everything from white rice to tofu, cha siu, drunken crabs, and xiao long bao, delving into what has become her life’s work. Finally, the door is ajar, she says, offering us her insights into the wealth of Chinese cuisine.

Chapters often start with a personal anecdote of a dish eaten in a particular place: “the top-ranking pot,” a soup of Jinhua ham eaten on the Bund in Shanghai in the company of a gentleman known as Mr. Crab; knife-scraped noodles in industrial Datong in northern Shanxi province. Dunlop zooms in and out, sharing the anthropological and historical origins of these delicacies and evoking the setting and feeling of each dish.

There are lists of ancient and modern cooking methods, starting with roasting and ending in steeping, by way of “exploding” stir-fries and “smothering” (cooking in a liquid, usually with a lid). Readers may want to hop on a plane to the West Lake after learning of the philosophy and food of her now-friend, chef-owner A Dai from the Dragon Well Manor outside of Hangzhou, who has dedicated himself to sustaining traditional cooking methods and supporting local producers.

There’s no one else doing what Dunlop does. For decades, she’s bridged the English- and Chinese-speaking worlds around Chinese cuisine theory and practice, winning awards along the way. With all her books now translated into Chinese to accolades, this new volume brings it all together as a theoretical complement and delightful read (or listen, as she herself exuberantly reads Invitation to a Banquet in its audio version.) I cannot recommend this book more highly.

Painting the Plate: 52 Recipes inspired by great works of art from Mark Rothko, Frida Kahlo and many more by Felicity Souter (Prestel Publishing / Penguin Random House, 2023). Reviewed by Luisa Giacometti, pictured above.

This book caught my attention at a recent visit to the gift shop at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Its author is a writer, artist and cook based in London, England, who blends art with good food. I like both, and agree that food can certainly be considered an art form in its preparation, ingredients, method of cooking and presentation. As I delved into the book, I was delighted to see how it was laid out. The author did extensive research; her book is as much art history as cookbook, all inspired by the art and unique food interests of the artists.

Souter has selected 52 artists notable for their unique connections to food. Each entry includes an art image from an artist, a write-up of the artist’s food interests and an easy-to-make recipe inspired by their artwork, ending with a beautiful visual image of the plated food. The recipes are categorized as Starters and Sides, Mains, Desserts, Drinks and Menu Planner.

She reveals that Jackson Pollock loved baking and would win prizes for his pies; Georgia O’Keefe wanted her food to be nutritious and would grow her vegetables and fruits or get them from nearby farms because she believed food helped her to power her creative mind and live longer, just like Pablo Picasso followed a strict diet for the same reason.

These captivating insights help us understand their choices, personalities and artistic style. I was surprised to learn how many of the artists were good cooks and collected recipes from their families and travels, or created their own recipes.

The recipes that the author presents are inspired by the artwork from the artists’ careers. These are simple to make, yet totally capture the essence of the artist. Some that I tried were Orange Custard Tart (Vincent Van Gogh) and Spinach and Feta Spiral Pie (Richard Long). I highly recommend this book. The art—and food—offer many hours of reading enjoyment.

Mrs Beeton and Mrs Marshall: A Tale of Two Victorian Cooks by Emma Kay (Pen and Sword, 2024). Reviewed by Fiona Lucas, pictured above.

The latest historical research about cooks and cookbooks from Emma Kay, this one an homage to two key Englishwomen. Kay says her “opinion was fairly resolved. Agnes Bertha Marshall was a neglected heroine … while Isabella Beeton stood as an impostor, a usurper of far more worthy heroines.”

Kay “intentionally tried” to research “largely from scratch,” to “analyse the relevant available primary sources” herself, and add “new snippets of information.” She largely achieves this goal by an outstanding search through many local newspapers, court records and Marshall photographs and letters unknown to previous writers.

She concludes that Beeton should be remembered for her progressive “contribution to the broader lifestyle field of the Victorian periodical,” not just as the plagiarist compiler of the best-known Victorian cookbook. She convinces us that Marshall was a truly enterprising businesswoman who rose above a crooked husband to become a creative “high priestess of cookery” and who regrettably is insufficiently acclaimed due to Beeton’s dominance.

Impressive though I find Kay’s research and plausible her assessments, she is ultimately undermined here by a severe lack of copyediting and proofreading. Shame on the publisher. Verbs are mismatched to nouns, critical dates are missing, people are introduced without explanation until pages later, paragraph subjects change without warning, quotations are uncited, items are missing from the bibliography, too many endnotes contain errors.

The countless typos are unbelievable: quoting an 1875 advertisement, for instance, Cavendish Square becomes Oven Dish Square! Several publication years are incorrect: Mrs Henry Lumpkin Wilson published Tested Recipe Cook Book in Atlanta in 1805; oops, that should be 1895.

In addition, Kay continually assumes readers already know certain facts, such as Beeton’s connection to the Epsom Grandstand. She flits between topics, circles back and forth, moves between time periods with no segue and often without providing dates. An example: preceding any introductory overview of Marshall’s life (dates, career, achievements, publications), Kay launches into Marshall’s children’s lives without first summarizing their number, order or dates, not even their names

Emma Kay is a seasoned and prolific author of well-received books and essays. This book reads, unfortunately, as if her first draft was accidentally printed

Dining out with History: At Atlantic Canada’s Historical Sites by Jan Feduck (Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd, 2024). Reviewed by Judy Corser, pictured above.

Ontario author and CHC member Jan Feduck’s delightful book explores Atlantic Canada’s dining traditions, historical context and recipes, providing a fascinating glimpse into lives lived in Canada’s past through the lens of the historic sites.

A life-long traveller interested in food history, Feduck uses her curiosity and experience to discover the food traditions of 20 of Atlantic Canada’s living museums. Although I lived in Annandale, Prince Edward Island, for a few years and knew about Kings Landing in New Brunswick—and, of course, the Fortress of Louisbourg—I had no idea of the many out-of-the-way historic sites around me. Two such sites are on Prince Edward Island: Orwell Corner Historic Village and Jean Pierre Roma National Historic Site. Feduck visits these, as well as others in New Brunswick, Newfoundland, and throughout Nova Scotia.

She begins with the Eskasoni settlement on the shores of Bras d’Or Lake in Cape Breton, a Mi’gmaq reserve created in 1832, and takes us along a 2.5-km forest path that shows visitors medicinal and food plants, smudging ceremonies and an opportunity to try Four Cents Bread and Eel Stew.

Recipes are included for these two dishes, alongside others ranging from Mock Cherry Pie to Nee’s Fish Cakes, Rappie Pie, Fish and Brewis and Tipsy Cake. Flummies and the aforementioned Four Cents Bread share the common ingredients of flour, water, baking powder or soda, to be “baked” on a stick or over a fire; fundamentally the same dish as the beloved fry bread or bannock of western aboriginal groups.

The unusual no-yeast Cinnamon Buns recipe from Sherbrooke Village is very much like the Acadian dessert Pets-de-Soeurs (Nun’s Farts!), made with a pie pastry-type dough and brown sugar, sometimes adding cinnamon as well.

Feduck prefaces most chapters with photos and brief stories. These well-researched fictional accounts of a day or event in the life of a person at the time are wonderful bonus walk-backs to the 18th or 19th centuries.

An enjoyable browse, Dining Out with History would also be a particularly special and useful resource or gift for a friend about to embark on a discovery trip to Atlantic Canada.

How Would You Like Your Mammoth? 12,00 Years of Culinary History in 50 Bite-Size Essays by Uta Seeburg, foreword by Max Miller (The Experiment, 2024). Reviewed by Dana Moran, pictured above.

Seeburg, former editor of the German edition of Architectural Digest, takes us on an entertaining romp in these 50 “bite-sized essays”, fast-paced snippets of culinary history that leave the reader turning pages, hungry for more.

In the opening essay, humans “cooked their way to the top of the food chain” by eating the bone marrow of mammoths, high in protein and supporting the growth of the brain. Amusingly, we also discover that members of a 1951 New York men’s club claimed to have eaten mammoth, until DNA analysis proved it was only green sea turtle.

The essays that follow have similarly interesting scientific tidbits: in the chapter on grain porridge, we learn that “wheat domesticated us” or that the barley diet of the gladiators allowed for some extra flab to protect internal organs from stab wounds, or how Alvise Cornaro, who wrote about the vices of immoderacy in 1550, nevertheless allowed for a pint of red wine a day.

Seeburg also reviews traditions that existed before science intervened, such as the early Roman trick of having a living animal fly out of dishes for some extra social cachet. Hilariously, medievals thought raw bacon could be used to cure wounds, both internally and externally. Monks served gingerbread to the needy to decrease grease on the teeth, before the perils of sugar for oral health were known.

Amidst these scientific food facts are other highlights of the culinary-history hitlist: the fact that “butter changed everything” with Varenne’s French sauces in 1651, that the oldest recipe ever written came from Babylonia in 1730 BCE, and the news that an omelette was the first thing to be prepared on television on the BBC.

There’s history beyond the Western tradition, as Seeburg informs us that Mongolian soldiers used their helmets to cook and introduced hotpot to China in 1200, which would become the national dish. She mentions that before 1500, curry—introduced by the Portuguese—contained no chilis. And in the concluding chapter, on the pandemic dinner, Seeburg further elevates food, stating that “sharing a meal together is the cornerstone of human existence.”

The essays are light, lively and short, but anything but fluff. They serve to provide the meat of the argument that “food harbours power and ruthless hierarchy” and that the discussion surrounding it has become increasingly politicized. This point is underlined by the contention surrounding borscht: in 2019, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs claimed that borscht was the national dish of Russia, while Ukrainian chef Ievgen Klopotenko claims that borscht makes Ukrainians who they are much as their language does. In July 2022, UNESCO named Ukrainian borscht an “intangible artifact of Ukrainian heritage.”

A Thirst for Wine and War—The Intoxication of French Soldiers on the Western Front by Adam D. Zientek (McGill-Queens University Press, 2024). Reviewed by Luisa Giacometti, pictured above.

The first things that caught my attention about this book were the title and the cover with splatters of blood and wine stains. Apparently, blood and wine became associated with energy and strength, vitality and power. I was intrigued how war and wine became companions.

The book starts off by introducing us to the First World War in France. The author describes well the bleak conditions of soldiers fighting in trenches, overwhelmed by the enemy and the ongoing grind of battle. The battles came at a cost to the soldiers, with physiological as well as psychological and emotional changes.

Wine (pinard, as it was called) was given to the soldiers as an antidote to the traumas of war, to bolster their morale and resolve to continue the fight. This required an immense amount of wine that was sourced not only from France but also Spain, Portugal and Algeria. The distribution of the wine to the soldiers was logistically planned (the daily system) and became an experiment in emotional and behavioural manipulation and control.

Although wine was important to the war effort, distilled alcohol (eau-de-vie) was also given before attacks. The distribution of alcohol was controlled while in the trenches, but when soldiers were on leave they abused the substance and became unruly, drunk and undisciplined. This required an intervention that included banning alcohol at the rear-front, banning sales to the soldiers and closing some of the existing alcohol shops or prohibiting the opening of new shops.

In addition, a surveillance system was set up to support compliance. By 1917, however, morale was at its lowest. Drunken soldiers mutinied, and army commanders had to take control of their alcohol consumption.

Zientek has undertaken extensive research here, delving into archival material, personal narratives and trench journals. He provides insight into how psychotropic drugs have been used and implemented during and after wars, not only in the French armies but also other fighting forces over the ages. Wars continue to rage, and although weaponry and logistics may have changed, the use of different forms of drugs is still prevalent in battles. I found this book captivating: a perfect marriage between history and the place of drugs in war.

Good Food, Healthy Planet: Your Kitchen Companion to Simple, Practical, Sustainable Cooking by Puneeta Chhitwal-Varma (TouchWood Editions, 2024). Reviewed by Maya Love (pictured above).

Toronto writer and food advocate Puneeta Chhitwal-Varma asserts that this book is her rallying cry to transform how we cook and what we eat. She invites readers to think beyond their plates and assume an easy-to-follow framework of “eating with benefits,” describing her practical and easy approach to a low-waste and earth-friendly lifestyle.

The chapters on eating to save the planet, reducing what we throw away, how to stock a good food kitchen, and recipes with insights and green tips shape the book’s organization. The more than 75 foundational recipes, while often Indian-focused, still represent an eclectic range of cuisines, many of which are vegetarian and often gluten-free, and are simple and delicious. The recipes also form a template to sourcing and preparing food with climate consciousness in mind, include cooking hacks and make the most of the ingredients people have on hand, which Chhitwal-Varma calls “pantry-forward.”

Referring to herself as, “an everyday food-waste warrior,” she adopts the mantra that less is more, dispelling the notion that climate-friendly cooking has to be overly involved or time-consuming. Chhitwal-Varma encourages us to adopt a more relaxed style of food shopping rather than a rigid menu plan and favours using up what we have on hand and taking into consideration the seasonality of ingredients, our budget, the recipes we enjoy preparing and what our families want to eat.

What complements the book and ties it together is the stunning photography by Toronto food stylist Diana Muresan. Some of the colourful recipes catching my eye are the jewel-toned jars of Sun-Fermented Vegetables, Japanese-Style Okonomiyaki, a Street-Style Bombay Sandwich, Railway Beef Curry (one of the meat dishes included), and a seemingly effortless sweet finale, a two-ingredient Yogurt “Mousse.”

Good Food, Healthy Planet is a lively and timely book that clearly outlines why our choices in the kitchen matter. Chhitwal-Varma offers us a call to action (the why) and then provides us a companion guide (the how) of making climate-smart kitchen choices and adding food diversity into our everyday lives. It is available for pre-order before its April 16 release date.

Bene Appétit: The Cuisine of the Indian Jews by Esther David (HarperCollins India, 2021) and Sweet Malida: Memories of a Bene Israel Woman by Zilka Joseph (Mayapple Press, 2024). Reviewed by Ivy Lerner-Frank (pictured above).

I’d never experienced anything like Jewish New Year Rosh Hashanah in New Delhi. In the middle of the synagogue’s morning service, there was a tea break. I was already used to tea breaks from my daily life in India—the morning and afternoon snack, sometimes heavy, is a ritual common across the country and across all religions. What I wasn’t used to was there being a snack in the middle of the otherwise serious proceedings, or what was being served.

We all trooped out to the social hall in back of the little post-modern synagogue, where tables were spread with plastic tablecloths. And on those tablecloths were platters of samosas, pakoras, and special chik-cha-halva, what Esther David calls a “rubbery sweet” made by those of the Bene Israel sect of mostly Mumbai-based Jews, a wheat-based sweet presented in a huge round low platter, cut into diamond-shaped lozenges and adorned with pistachios and almonds. It was chewy, fragrant, and delicious.

Author Esther David travelled around India, visiting the five dwindling communities of the Bene Israel, Cochin Jews of Kerala, Baghdadi Jews of Kolkata, Bene Ephraim of Andhra Pradesh, and the Bnei Menashe of Manipur in India’s Northeast to chronicle these culinary treasures in this book. At each stop, David met with community members and leaders, asked questions in survey format, and compiled their answers and their recipes along with her impressions, creating a portrait of the now less than 5,000 Jews still residing in the country. (The majority of Indian Jews have emigrated to Israel over the past years.)

David chronicles the details of how each group celebrates Jewish holidays, the particularities of their dress, the creative ways communities observe the dietary laws—such as eating fish and vegetarian food when there is no kosher meat—and the unique dishes, like chik-cha-halva, that characterize each individual group. For those who are only familiar with Eastern European Ashkenaz cuisine, the recipes here, many which we might rightfully associate with contemporary Indian cooking, will intrigue. David’s collection of these recipes and grouping them according to the communities was a labour of love.

Spices, of course, play a big role in the food of the Indian Jews. Likewise, with dietary laws prohibiting the consumption of milk and meat together—and the easy availability of coconuts in most parts of the country—there is a considerable use of coconut milk rather than dairy in many recipes calling for creamy sauces.

Other cookbooks and culinary histories such as Claudia Roden’s The Book of Jewish Food contain Indian Jewish recipes that have been standardized and tested more thoroughly; for example, the chicken dish called chittani here is less clear and more difficult to follow than the chittarnee that Roden explains more clearly. David’s book, available in North America but published in India, is written more for an Indian audience and may leave some readers not familiar with techniques such as “three whistles” for pressure cooking or tilkut masala, a red chili and sesame paste, behind. Nevertheless, Bene Appétit is an important contribution to the culinary history of this group of diaspora Jews, whose traditions are now virtually forgotten.

One writer who has not forgotten the traditions is Bene Israel poet Zilka Joseph, whose slim volume Sweet Malida refers to the dish malida, a platter of poha, or flattened rice, made for thanksgiving and served on special occasions. Joseph’s poems invoke reverence for Eliyahu, the prophet revered by members of the Bene Israel community, and bring to life the Bene Israelites’ reverence for nature’s sweet bounty.

In her poem Eliyahoo Hanabi, Joseph brings the dish to life: “Let us heap the sugar-sprinkled poha / tall as a pyramid, mixed with shredded / coconut, precious dried fruit and nuts / scented with the most fragrant / of spices. Oh Elijah, can you taste / the nutmeg, the cardamom, the freshly / sliced mangoes, guava, chikoo, apples and / bananas arranged like garlands?”

Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen by Rebecca May Johnson (Pushkin Press, 2022). Reviewed by Ivy Lerner-Frank (pictured above).

“The word I encounter most often when I tell people I am writing about cookery is lovely. It makes me want to tear my hair out. Often, I temporarily lose the power of speech.” Rebecca May Johnson pulls no punches in her experimental first book Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen. This is a thought-provoking, consistently varied book, fascinating in its breadth and its unconventional approach.

Johnson, now an editor at the British online magazine Vittles, had been working in Germany on her doctorate on the subject of The Odyssey, far from her home in Britain. The PhD took her six years — felled by anxiety for much of it — during which she undertook many repeat “performances” of cooking Marcella Hazan’s recipe for Tomato Sauce with Garlic and Basil. And what else to do but document this passage? Some may feel overwhelmed with too much information about Johnson’s self-observations, but she is never merely going through the motions.

“I feel discomfort at being constrained under the sign of ‘lovely,’ located on the side of the so-called virtuous,” Johnson says. As she explores the relationship between body and language, between recipes and improvisation in the kitchen, Johnson brings us along in a brutally honest journey through classic philosophy, pop culture, Marxist theory, feminist principles, the meaning of Nigella Lawson’s indulgent, sensory approach to cooking and eating, and even a foray into Mrs. Beeton’s 19th century recipe for Fried Sausages.

“The minimalism of the recipe text is in a dialectical relationship with the total possible edible world and everything I might do with my body.” Johnson writes, dismantling pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald W. Winnicott’s exhortations to play in the kitchen and not follow recipes. (This in contrast to Mrs. Beeton’s cooking instructions, exhorting the cook to prick the sausages and “move the pan about.”

In numerous interviews, Johnson refers to the more theoretical first half of the book and the fact that she wrote the second half by hand, editing it while transcribing. “The recipe is a method of navigation,” she writes, “a method of seeing or seeking what is beyond me.” The recipe is absolutely the point of departure here, and she plays with it – extensively. As Johnson deliberates, witnessing and describing her own food obsessions as well as those of others, she ties her apron tight, bringing us along in her complex, thoughtful and utterly creative volume.

Zaatari: Culinary Traditions of the world’s largest Syrian refugee camp by Karen E. Fisher (Goose Lane Editions, 2024). Reviewed by Ivy Lerner-Frank, pictured above.

“Who has pictures of food on their phones?” This is just one of the questions that Karen E. Fisher, the author of this remarkable volume, asked the 90 participants attending a workshop to explore the interest of Syrian refugees living in Zaatari camp in Jordan. Virtually every attendee’s hand shot up, confirming what Fisher already knew: food, and the memory of food, was an inseparable element of identity for camp residents.

This is a comprehensive volume that richly rewards the reader, be they cook, anthropologist, historian, geographers, art lover or just plain armchair traveller. Organized by life cycles—birth, death, marriage and everything in between (there’s a special focus on wonderful ftoor breakfast foods found in the camp)—the book weaves stories of camp residents alongside photographs of the dishes and the chefs, illustrations and illuminations. The result is a remarkably comprehensive picture of life in this camp of over 80,000 displaced refugees, “dream[ing] of living in Syria’s houses, smelling its perfume, and helping it live again.”

One of the challenges of writing this book was the resident cooks’ lack of familiarity with what a cookbook—or a recipe—was. Fisher, a Newfoundland-born “design ethnographer by way of librarianship” working for the UNHCR at Zaatari, realized what a task she had on her hands when she called that initial meeting in 2015. Eight years later, the book is reality, and recipe quantity descriptions such as “the size of a chicken head” have been ably interpreted and standardized so as to be understood by readers, though, to be fair, “the size of a chicken head” would be clearly understood by the denizens of Zaatari.

I loved the book’s many anecdotes, like the fact that bread is the only utensil needed to eat jazmaz—eggs poached in tomatoes—or that one should never offer an even number of dates when serving coffee to a guest. I chuckled at the fact that Zaatari have a special hand signal for “Come to my house—let’s make kibbeh.”

The recipes, ranging from hummus to shish taouk, rummaniyeh (eggplant and lentil with pomegranate molasses) and rgagah, a spectacular four-layered pastry with meat and caramelized onions, are clearly written, though I will say experienced chefs would be the most comfortable with this book. There are numerous varieties of chai and other drinks on offer, including some to nourish new mothers, and beautiful intricate pastries like maamoul to eat alongside them at tea time.

Historians and cooks alike will take pleasure in this lovely volume.

A History of Bread Consumers, Bakers and Public Authorities Since The 18th Century by Peter Scholliers (Bloomsbury Academic, 2024) Reviewed by Sher Hackwell (pictured above).

A History of Bread is part of Bloomsbury Academic’s Food in Modern History: Traditions and Innovation series. Author Peter Scholliers is an academic with expertise in European—particularly Belgian—food history. Because of his earlier research, he centres the content around Belgium’s baking history. The book was originally published in Dutch in Belgium in 2021.

Rather than a chronological format, the principal text is split into three tidy chapters: Bread Eaters, The Bakers, and The Authorities, each interconnected, yet each playing a leading role.

Bread Eaters examines class disparities, buying habits and historically high bread consumption. A handy chart illustrates how mid-18th-century eaters spent 50% of household income on bread; fast forward to 2020, and bread expenditure is down to 1%. This section’s research was primarily found through documentation concerning bakers and authorities, as, historically, eaters were essentially voiceless.

Eighteenth and 19th-century engravings of boulangeries, bread and equipment animate The Bakers chapter. My favourite is a somewhat grisly early 20th-century poster on labour rights depicting the Grim Reaper taunting a toiling baker.

The cover image, a 1930s Belgian monotone, depicts a line of mindful production bakers—a profound yet appealing image that conveys the importance of bread as a universal foodstuff. There are no additional photographs; Scholliers relies on tables, appendices and figures (charts and engravings). I would have liked more engravings, as their intricate details add historical value.

Fortunately, Scholliers’ descriptive writing style makes up for it. His comprehensive approach guides readers through bread’s tumultuous history—wars, petitions, uprisings, artisanal bread, assizes, mechanization, regulations and bakers’ wages.

A History of Bread is a textbook, not a cookbook, but even so, it motivated me to dust off the banneton, feed my levain, and bake a loaf of scratch-made bread.

Eating Like a Mennonite by Marlene Epp (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023). Reviewed by Judy Corser, pictured above.

This book is founded on both the author’s deep scholarly work and her lived experience. At a presentation to seniors on Mennonite practices, the answers to her question “What comes to mind at the word ‘Mennonite’?” were instructive: “Lots of meat, potlucks, pig butchering, abundance and bounty, eating too much, big gardens, frugality, eating ‘from scratch’, home cooking… meat, potatoes, vegetables, preserving food.”

Food, food and more food is central to the perception of Mennonite foodways, yet equally important is how the group’s food culture defined the role of women, how the diaspora of Mennonites leaving Europe for Canada, U.S.A., Mexico, Paraguay and missionary work in Republic of Congo, India, Laos and Cambodia, among other countries, adopted foodstuffs wherever they found themselves.

Epp describes how Mennonite recipes were often adapted to the food available locally, and the subsequent fondness that developed for rice and curry, cassava, eggplant, hot peppers and even, occasionally, insects. Meat appears to have been dearly missed, as one missionary in Congo expressed her frustration with eggplant prepared in the manner of meat and “was delighted when another missionary and a hunter brought them canned buffalo thighs.”

Epp does not restrict herself to Mennonite food and recipes in this volume. She touches upon the group’s history of religious persecution, scarcity and deprivation that may have contributed to the Mennonite need for abundance, letting no one leave the table hungry. (There are a few recipes, one for the essential zwieback, others for borscht and tamales.) Epp discusses the gendered (female) role of food preparation and responsibility in the Mennonite community and introduces the idea that not all Mennonite women may have been happy with being restricted to the kitchen.

The children of Susanna Kehler Wiebe “described fondly the Russian-Mennonite foods she prepared for her husband and ten children, but also noted that she often cried while she cooked and was always the one to eat last and take the smallest helping.”

The foods widely thought of as Mennonite foods—zwieback, borscht, cabbage rolls, chicken soup, vereneki (pyrogies), fruit soup—were eaten by many other Eastern Europe ethnic groups: Russians, Ukrainians and people of the Balkans. My own maternal grandmother’s menus contained all the above, and her ancestors were German-speaking immigrants to North America who came not from Germany, but from Russia and are known as “Germans from Russia.”

Anyone who cares to explore this deeply significant area of Canada’s foodways would find Epp’s book worthwhile. It is comprehensive, extremely interesting and very readable.

Tenderheart: A Cookbook About Vegetables and Unbreakable Family Bonds by Hetty Lui McKinnon (Penguin Random House Canada, 2023). Reviewed by Ivy Lerner-Frank, pictured above.

“This is a book about my favourite vegetables, though some of them are technically fruits,” writes Hetty McKinnon in the first pages of this vegetable-based cuisine masterpiece.

Australian-born, New York-based McKinnon dedicated this cookbook to her father, who passed away when she was 15, a moment that predictably cleaved her life into a before and after. A vegetable seller in Sydney’s Flemington Markets, the legacy of her father’s Cantonese culture and the story of his life loom large in this comprehensive tome. The stories she paints of family life, her father’s passing and her mother’s adjustment after the loss of her spouse are infused with loving memories, gifted writing and simply plated, very beautiful food.

I’ve alternated my time with Tenderheart between cooking from the book and simply opening it at random with the deliberate intention of generating delight. Tenderheart does not disappoint on that scale: it’s beautifully produced, with gorgeous smooth paper and images of food styled and photographed by McKinnon herself. I’ve been most drawn to the photographs of vegetables that introduce each chapter, always placed in and around a simple Chinese beige-and-blue pot at the centre of the image. Sublime.

From Asian greens to zucchini, with detours for cabbage, carrot, tomato, and even taro, an unsung root vegetable McKinnon uses to make gnocchi, she shares a dizzying range of recipe styles, from Asian-focused to Italian-adjacent, plus noodles, rice, dairy- and vegan-based offerings.

As a lapsed vegetarian who now includes meat in my diet, what I particularly love about Tenderheart is that it’s not about vegetables as sides dishes. From tomato and gruyere clafoutis to miso mushroom ragu with baked polenta, each recipe is umami-rich and can stand alone as a main for any kind of meal. Recipe instructions are clear and well-organized, many of the ingredients are pantry or seasonal staples (brussels sprouts, for example) and consistently offer maximum flavour with a minimum of fuss—or pots and pans. This is home cooking, realistically portrayed.

The first recipe I cooked from the book was Broccoli Forest Loaf, with broccoli spears beautifully suspended in batter. A moist, savoury scone in loaf form, this was easy and fun to make. I’ve since made Kale with Orzo, Garlicky Sweet and Salty Pumpkin Seeds, and can’t wait to try Walk Away Tomato Sauce with Pici Pasta and Soy-pickled Tomatoes with Silken Tofu. McKinnon makes it all seem accessible, and it’s definitely all delicious.

New Year’s resolutions may fade as February approaches, but if eating more healthily in 2024 is on the agenda, this is a book well worth getting. I had no idea how much I would fall in love with it, but now I’m hooked.

National Dish: Around the world in search of food, history, and the meaning of home by Anya von Bremzen (Penguin, 2023). Reviewed by Ivy Lerner-Frank, pictured above.

“I’ve reflected much along my journey how certain dishes get recruited to express their country’s glorified inclusive identity – literal recipes for national unity,” says Anya von Bremzen in the Oaxaca chapter of her myth-debunking book, National Dish.

Von Bremzen, a triple James Beard award-winning food writer and historian, leaves her homes in New York and Istanbul to explore the origins of dishes and ingredients around the world: pizza, pasta and pomodoro in Naples; ramen and rice in Tokyo; tapas in Seville; maïz, mole and mezcal in Oaxaca; pot-au-feu in Paris; meze in Istanbul, and borsch, the disputed dish of her childhood in Russia, back in New York.

With a beautiful cover drawn by the beloved New Yorker comic artist Roz Chast, readers may be deceptively lulled into thinking that this is a light book about various international dishes. However, as von Bremzen reiterated in her recent talk with the Culinary Historians of New York, this is a book about nationalism and identity, not a cookbook. While the focus of each chapter is indeed on specific dishes, von Bremzen’s animated prose invokes history, mystery, myth and misrepresentation as she dismantles commonly-held notions regarding the origins of various foods. Von Bremzen builds her case that “the local and global feed off each other,” as she said in her recent talk, and that we have a “knee-jerk reaction to define what is national.”

Von Bremzen’s research, engaging interviews and no-nonsense approach are coated in an entertaining narrative that has just enough lightness to propel each chapter forward with vigorous discussions of stereotypes (terms like orientalism and exoticism in the chapter on Seville, for example). As the reader travels along with her and her husband Barry around the world, she builds her case: “I want people to think: What is a nation? What is a national dish? It’s so complex,” she says, “and I will take you through all those rabbit holes in my book.”

The most personal and poignant discussion comes in the epilogue, where von Bremzen, a Russian emigré who had always loved her mother’s Jewish-style borscht, comes face to face with Ukrainian friends over a bowl of soup. As she confronts the actions of her former government, the question of ownership of borsch (with no t at the end) “hangs in the air like an accusatory pall.” It is here that her exhaustively investigated book truly hits the mark.

The Food Adventurers: How Around the World Travel Changed The Way We Eat by Daniel E. Bender (Reaktion Books, 2023). Reviewed by Elka Weinstein (pictured above).

One of two books published in 2023 by Daniel Bender, the Canada Research Chair in Food and Culture, a professor of food studies and history, and the director of the Culinaria Research Centre at the University of Toronto.

Drawing mainly on travellers’ accounts, Bender asserts that tourism popularized certain ideas about “foreign food,” and that tourists mostly did not eat local foods, unless they were forced to do so, or on a dare. Travellers who deliberately set out to partake of foreign food, as the “food adventurers” of the title, mostly did not change their minds about the edibility of those foods, unless, like Juanita Harrison, they were able to “pass” as native.

The premise of Food Adventurers is that food tourism (via Cunard Steamlines, Pan Am airlines and so on) and the accounts by travellers who wrote about their adventures in eating strange, new foodstuffs changed world cuisines. Various foods that were seen as either disgusting or disease-causing were tasted and smelled, pronounced edible or not, and finally absorbed (or not) into Western cuisines. English and American perceptions and experiences of “foreign” edibles such as mangosteen and durian, were either reinforced or transformed into potentially profitable royal treats.

For me, the most interesting point that Bender makes is that although culinary tourism has become widespread, partly due to “food adventurers” like Anthony Bourdain (a quick Google search of “shows like Anthony Bourdain” yields 13 titles) tourists are still adjured not to drink the water and not to experiment with “foreign foods” lest they contract “Delhi Belly,” “Montezuma’s Revenge” and similar ailments. I would have liked to have seen this idea explored in more detail, perhaps through more 20th-century travellers’ accounts.

World cuisines may have changed with the addition of strange (to the West) foodstuffs, but perceptions of unfamiliar food and drink (mainly) in the global south seem not to have changed at all. Why this is true is the most interesting idea for further exploration.

Why Fast? The pros and cons of restrictive eating by Christine Baumgarthuber (Reaktion Books, 2023). Reviewed by Luisa Giacometti, pictured above.

To fast, or not to fast? That is a question many people ask when considering healthier wellbeing options. Christine Baumgarthuber answers this question, along with much more information on the history and benefits of fasting.

She points out that we live in an environment with overabundance of food at a relatively low price, making it easier to overindulge. Moreover, she says, most of our food is now ultra-processed. Together with a lack of exercise, this leads to many health problems, she believes, putting forward the view that fasting is one way to counteract the excesses that build up in our body and bring it back to balance by willfully observing a period of abstinence.

Baumgarthuber describes the metabolic and physiological workings of the inner body, outlining the thinking and theories of many scientists over the ages and their contribution to the topic. She also writes about the different periods of famine or experimentation that led to more understanding of how the body reacts under such conditions, such as the Turnip Winter of 1916–1917 and or the Minnesota Starvation Experiments of 1944 to 1945.

In a chapter on the promise of fasting for weight loss, Baumgarthuber provides insights into a variety of diets, such as milk alone for six months and fasting between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. Physicians tried these options out on themselves and their patients, ending up with mixed results, both physically and mentally, depending on the individual.

Although I found the information of interest, Baumgarthuber’s personal experiences were of more value to me. The author herself practices a form of 16:8 fasting, whereby she confines her daily eating to two meals taken within an eight-hour window. She finds that she now has a portion of her life back, as she doesn’t have to cook in the evening and can turn her attention to reading, sketching, sewing or anything else she fancies.

Baumgarthuber offers suggestions to assist those with flagging fasting willpower—like apps such as MyFast. There are now custom fasting programs available through different clinics geared to one’s unique physiology, as well as books and social media first-hand accounts. My advice? Read the book, do more research, experiment, and talk to your doctor.

The Gilded Age Cookbook: Recipes and stories from America’s Golden Era by Becky Libourel Diamond (Globe Pequot, 2023). Reviewed by Sher Hackwell, pictured above.

While The Gilded Age Cookbook is not the companion to Julian Fellowes’ Gilded Age series, fans will devour the cookbook’s recipes and stories of America’s Golden Era as fast as one can say Christine Baranski.

It’s as much about the period’s inventions, traditions and etiquette as the recipes. With two previous culinary history books, author, historian and librarian Becky Libourel Diamond has 19th-century American opulence covered. The book’s rich suede-finish cover reveals full bleed autochrome-style images with understated props that allude to the time. Think a casually arranged bowtie alongside a beaded silver tray bearing glasses filled with Fish House Punch. Historians will welcome the highly detailed illustrations courtesy of Mrs. Beeton’s books, among others.

The 19th-century recipes are a collection of culinary classics—Lobster Salad, Lemon Meringue Pie and Fried Chicken—peppered with unusual dishes like the holiday specialty Devilled Spaghetti, and Jumbles: ring-shaped, spiced shortbread. Recipes appear to be primarily adapted from period cookbooks, cooking schools and familiar regional fare, like Boston Brown Bread.

Considered backstories are incorporated for each recipe via header notes or in-depth descriptions like Mrs. Vanderbilt’s OTT dishes served at her opulent balls, i.e., a “pheasant game pie held up by deer’s antlers, with two rabbits playing cards underneath.” And, as it was the age of railroad magnates, the author includes an explainer on Pullman car dining, cooking and the origin of the Pullman Loaf.

Diamond hits the mark by effectively marrying her recipes with all the scintillating details of high-society socials, luncheons, debutante balls, and even special events for affluent animals. Oh, to be that proverbial fly-on-the-wall!

The Lost Supper: Searching for the future of food in the flavors of the past by Taras Grescoa (Greystone Books, 2023). Reviewed by Maya Love (pictured above).

In The Lost Supper, Taras Grescoe makes the case that, rather than relying on innovation-focused agriculture, we need to investigate our collective pasts to find our way forward. He argues that we should be looking to sustainable foodways and traditional ecological knowledge. By selecting a variety of nearly forgotten foods from around the world that tell the stories of civilizations, Grescoe aims to show readers that there is hope in turning to old foodways.

As a prelude to writing the book, Grescoe starts out in his home city, Montreal, asking himself the daily all-consuming question, “What am I going to eat?” Not being a fan of processed food, he’s already delved into urban home economics to explore the diversity of foods by making ferments and trying his hand at balcony agriculture. Grescoe becomes focused on searching for forgotten foods and embarks from Montreal on an archaeological food quest travelling through history. An adventurous eater, he is guided by his research on a round-the-world pilgrimage to discover nine lost, endangered and ancient foods, representing and spanning our half-million-year history as a species.

Stepping away from industrial food, Grescoe interacts with farmers, agriculturists, food scientists, experts in ancient cookery, historians, archaeologists and small local food producers. Throughout the book he introduces readers to surprising foods we have forgotten about.

There’s ham from a 500-year-old herd of black-footed Spanish pigs on an island off the coast of Georgia, edible aquatic insects in Mexico City, olive oil from 2,000-year-old wild olive trees on the shores of the Mediterranean, Yorkshire Dales raw-milk hard cheese from critically endangered British dairy cattle, garum (the secret umami ingredient of Ancient Roman fish sauce), Neolithic baked flatbread, the long-thought-extinct silphium, and even purple cama flowers in Oak Bay, British Columbia, where since before colonization, Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest ate the bulbs of camas, now being revived as a crop.

The message of the book is that in nutritional diversity lies resiliency, and that by adding diversity to our diets we are contributing to the sustainability of natural ecosystems. Grescoe concludes that “to save it, you’ve got to eat it.” The Lost Supper provides adventures, travel writing, history and first-hand culinary experiences that will appeal to a wide range of readers.

New Indian Basics: 100 Traditional and Modern Recipes from Arvinda’s Family Kitchen by Preena Chauhan & Arvinda Chauhan. (Penguin Random House Canada, 2022). Reviewed by Ivy Lerner-Frank (pictured above).

This is a book about spices, family and cooking with love, written by a mother-daughter team. Arvinda Chauhan started a cooking class in Hamilton after her pakoras were a hit at a local community fundraiser 30 years ago. From there she opened a cooking school and along with her children Preena and Parekh, a small-batch spice-blend company.

“Without spices, there is no Indian cooking,” Preena writes. This book, nominated for a Taste Canada award in the Regional Cultural category, is a comprehensive volume that contains everything you could want to know about spices: from grading and origin to storage tips and shelf life. The authors explain layering, how to temper heat levels, and how whole spices release their flavour at each level. They share techniques such as dry roasting and spice-sprinkling (“just like a sprinkling of gold”), how to pair spices, balance flavours with a pinch of salt and perhaps one of the most important tips ever: that curries mature with time.

After the spices, the cooking: how to cook rice the Indian way (basmati or Patna), special tools for cooking, storing, and eating, and how to serve—and eat—an Indian meal. The material is presented clearly and comprehensively, providing wisdom that the home cook can readily apply to their own practice.

Advice like preparing onions and herbs as well as ginger and garlic pastes in advance, taking advantage of pressure cookers, food processors and stand mixers is solid, but did you know what a good idea it is to have two sets of measuring spoons nearby, one for dry and one for wet ingredients? This common-sense approach underscores that these women have been cooking for years. Their commitment to sharing their knowledge makes this book a very worthwhile read.

The Chauhans start the recipes with foundational dairy products: ghee and yogurt (dahi), moving on to spice blends, beans, street foods, lentils and beans, and mithai: sweets and desserts. My favourite chapter—after having lived in India for almost ten years—is the Indian brunch and eggs section. I have a thing for anda bhurji (spicy scrambled eggs), masala omelette (with toast) and besan pudla, a chickpea flour pancake with chilis and cumin that I could never get enough of in Delhi. The chutneys that go with these breakfast treats—tamarind date chutney, mango peach chutney, minty green chili chutney and hot chili tomato chutney—all bring back happy memories.

This book is like a warm garam masala hug. Anyone interested in Indian home cooking, from north to south, will find it engrossing, enlightening and delicious.

Only In Saskatchewan by Naomi Hansen (Touchwood Editions, 2022). Reviewed by Abbey Stansfield (pictured above).

In this dynamic look into Saskatchewan’s food scene, author and self-proclaimed foodie Naomi Hansen travels the province to collect recipes and narratives found “only in Saskatchewan.” In an attempt to provide a well-rounded narrative, the author has gone to the far reaches of the province to interview the people that make each of these food establishments so special. Each recipe in this book, nominated in the Regional/Cultural category in this year’s Taste Canada Awards, is contributed by an iconic food establishment and prefaced with the history of why diners treasure it.

Peppered with beautiful images of the diverse landscape Saskatchewan offers, this book is a curated collection of unique dishes containing locally sourced ingredients. The chapters are broken up into five different regions of Saskatchewan: North, Central, Saskatoon, Regina and South. As I read through the different chapters I found the recipes challenged my expectations of prairie cuisine. Recipes I had not anticipated, for dishes like Vietnamese Lemongrass Beef Stew, appear alongside the more expected recipes of Bison Bannock Pockets with Cranberry Marinara.

Some recipes contain ingredients that are uniquely Saskatchewan staples unlikely to be seen in local grocery stores in most of the country. Acquiring ingredients like bison, Saskatoon berries, and sea buckthorn berries may seem daunting; however, Hansen has provided a sourcing guide at the end of the book to help find tricky ingredients and has suggested substitutions where possible. These additions helped alleviate initial doubts that recipes will be replicable outside of Saskatchewan.

I made the decadent Eatery on Main’s Ferrero Rocher Cheesecake recipe as a first test recipe from the book. From the onset I was wary of being able to reproduce the delicious looking cake in the picture. The recipe defied what I had come to expect from a cheesecake recipe, with no water-bath baking, no precook of the base or addition of cornstarch to the cheesecake batter. However, the end result was a beautiful cheesecake that captured the rich chocolate and hazelnut taste of a Ferrero Rocher chocolate.

I believe after working through the recipes in this book that they have been written to provide the home chef a means of recreating these beloved and iconic dishes in their own home kitchen.

This cookbook is a glimpse into a food scene not widely covered. It provides pictures of the beautiful landscape of Saskatchewan, wonderful eateries, and the stories of the hardworking people providing the recipes. Hansen has managed to highlight that histories of where our food comes from can be just as important as the recipes themselves.

The Two Spoons Cookbook: More than 100 French-inspired Recipes by Hannah Sunderani (Penguin Random House, 2022). Reviewed by Ivy Lerner-Frank (pictured above).

“In a culture where fromage, foie gras, and charcuterie are everyday staples, a plant-based diet was not always celebrated,” says blogger, recipe developer and vegan home cook Hannah Sunderani. Sunderani’s experiences living in Lille, France, as a vegan (read: challenging!) inspired her to explore how to adapt classic French recipes to her own dietary requirements.

Sunderani has over 155,000 followers on Instagram: she’s definitely tapped into what the people want. It’s a complete aesthetic she’s offering, with a breezy white kitchen, a chill vibe, and her husband Mitch (a self-avowed terrible cook, which Sunderani only lightly disputes) making periodic appearances on her YouTube channel to show that these recipes are user-friendly and delicious.

The book—shortlisted for the Taste Canada award in the Health and Special Diet category—delivers on this premise, with beautifully photographed plates of what Sunderani calls everyday dishes. There are definitely a few challenging projects, like vegan croissants, but Sunderani provides a range of options, from classic French (croissants and crêpes), contemporary vegan (turmeric lattes and winter bliss bowl), as well as Moroccan dishes for her readers.

Sunderani never proselytizes her vegan lifestyle in the book, though she does provide some funny anecdotes about how she was treated in France upon announcing at restaurants that she eschews animal protein and dairy. (She was once presented with a half carrot as a main; she wondered what happened to the other half, as do we.) Her recipes are straightforward and well laid out, with tags at the top of each recipe indicating whether it is gluten-free, grain-free, oil-free, soy-free, no added sugar, or refined sugar-free. For those who need to be alert to these kinds of issues, it’s a very helpful addition.

The book is a comprehensive resource for those who are embarking on a vegan approach to eating. In a detailed chapter on kitchen tools and equipment, Sunderani outlines what’s needed for each recipe, from microplanes to measuring tape to sieves. Her pantry suggestions are excellent, clarifying what kinds of oils, butters and acids she uses in her recipes.

I also really appreciated the section on how to make several varieties of dairy-free milks, including a super-quick oat milk and almond milk. These are all building blocks for her recipes, and well worth reviewing before diving into the recipes. I also really liked Sunderani’s dinner-menu page, with options including dinner for two, dinner for entertaining, dinner with besties, and family fun.

My eyes were drawn to the colourful hummus recipes—golden roasted carrot hummus and pink beet hummus—her balsamic roasted beets with toasted pine nuts and homemade “blue cheese.” But I’ll confess: the chocolate peanut butter truffles, and lemon tart (with coconut milk) look wonderful, and I’ve bookmarked those for this fall.

Heaven on the Half Shell, Second Edition by David George Gordon, Samantha Larson & Maryann Barron Wagner (University of Washington Press / Touchwood Editions, 2023). Reviewed by Judy Corser, pictured above.

As Irish satirist Jonathan Swift remarked: “He was a bold man who first eat an oyster.”

Every lover of oysters has a story to tell, and mine is standing in an oyster bed at half-tide on Jedediah Island (British Columbia), picking up oysters to be opened by my companion, who possessed much better technique, and then popping them into my mouth. He was skeptical: his preference was for roasted or fried.

In July? What about those months with the R? A short distance across the water, an oyster farm on Lasqueti Island was busy harvesting, so that was good enough for me: the oysters were safe to eat. According to the authors, this is the “R month” myth (harmful algae such as Alexandrium, Dinophysis and Pseudo-nitzschia do produce toxins that accumulate in mollusks such as oysters, mussels, clams and other filter-feeders; caution is advised.) Historically, wild oysters were not in their prime during May, June, July or August, but that is because these are spawning months when the oyster devotes its energy stores to producing eggs and sperm at the expense of flavour.

Heaven on the Half Shell is a bible for all interested in oysters and oyster farming today. Produced with a Washington Sea Grant, it primarily focuses on oyster-producing American states, including Washington, Oregon, Maine, Massachusetts and Maryland, with some information on the lesser-known Alaska oyster-farming industry.

Slurping happily on the shores of Jedediah Island, I had no idea what I was slurping up! I now know there are many kinds of oysters in addition to the slow-growing native wild Olympic oyster (Ostrea lurida). The Japanese or Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) grows larger and faster than its wild cousin and today is the main oyster harvested in the Pacific Northwest. In addition, just as there is one cow but many kinds of cheese, there are many oysters to satisfy the most delicate of palates: Eastern (Crassostrea virginica) was introduced from New England; the Kamamoto (Crassostrea sikamea) came from Japan after World War II and said to have a more refined taste than Pacific oysters “with a subtle melon-tinged aftertaste.” European Flat (Ostrea edulis) is said to have a “flinty or slightly metallic” taste.

There are only rare references to anything Canadian in this otherwise very comprehensive volume: Fanny Bay is mentioned, where oyster farmer Keith Reid “created” the Kusshi (“precious” in Japanese) by “tumbling” his growing Kumamoto oysters in Norplex bags, the tumbling action resulting in what some call “the Kobe beef of the molluscan trade.” Kusshi—flipped—oysters are also marketed as Shigoku (“ultimate” in Japanese).

This volume is also filled with wonderful photographs, historical and contemporary, and a wealth of recipes, from Hama Hama Oyster Bread Pudding to Oysters Baked with Hazelnut-Herb Butter, to Tadich Grill’s Traditional Hangtown Fry.

Baking Yesteryear: The best recipes from the 1900s to the 1980s by B. Dylan Hollis (Penguin Random House, 2023). Reviewed by Luisa Giacometti, pictured above.

A treasure trove of vintage recipes from a social-media star who has chosen the best from among the hundreds he’s tried—then thrown in a section entitled The Worst of the Worst.

Hollis’ project came about during the COVID lockdown. A musician who was taking classes and rehearsing online with no one to speak to, he turned to TikTok and uploaded various videos before trying his hand at a baking video: Pork Cake from one his vintage cookbooks. He accomplished this with no cooking or baking knowledge, but he captured the interest of viewers who wanted more, and the rest is history.